Can Norway demonstrate the difference that its aid money makes to the lives of poor people in developing countries? This is the question that Itad, along with its Norwegian partner CMI, was asked to answer in its ‘root and branch’ evaluation of results measurement within the Norwegian Aid Administration which was launched in Oslo last week. Based on the year-long study we had to conclude, no, it can’t. The report is wide ranging so there is a lot to chew over, but here are just a few points of note (the full report is here and a 2 minute YouTube clip on the key findings here).

The need for system wide change

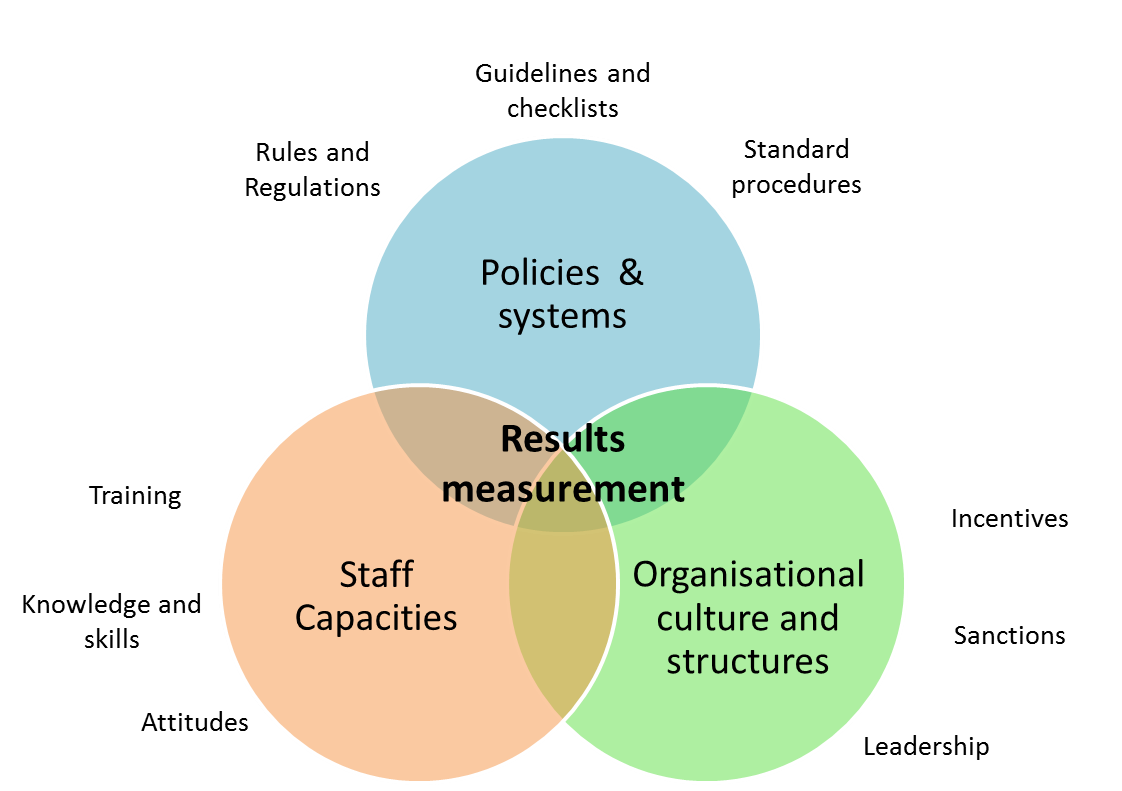

We were at pains in the report to emphasise that tinkering around the edges of the Norwegian grant management system will not make a difference. What we identified was a dysfunctional system and what is required is system wide change. We used an analytical framework for the evaluation that viewed results measurement as a product of a number of interlinked issues: policies and procedures, staff capacities, systems and structures, organisational culture, leadership, and incentives and sanctions. We found deficiencies in all these areas.

We found a system in which there was a lack of coherence in the procedures for results measurement, inadequate guidance around key areas of results measurement, inconsistent leadership on results, inadequate incentives for staff, and an organisational culture in which concerns around being partner led have held back constructive dialogue about results measurement.

We found a system in which there was a lack of coherence in the procedures for results measurement, inadequate guidance around key areas of results measurement, inconsistent leadership on results, inadequate incentives for staff, and an organisational culture in which concerns around being partner led have held back constructive dialogue about results measurement.

Presented with this array of reforms, the instinct is of course to go for the easy wins and produce a new handbook, manual or set of guidelines, but in the absence of the other changes, all this is likely to lead to are more documents that sit on shelves gathering dust. Changes to policies and procedures have to go hand in hand with changes to culture, incentives and leadership.

Designing a quality assurance system that is consistent, but flexible

Another finding was that Norway’s approach to quality assurance is too ad hoc. In most cases the person managing the grant decides whether a results framework or grant level evaluation should be quality assured. This highly flexible approach leads to inconsistent quality in how results are measured.

In a system in which staff are managing over two thousand grants in year, all of variables sizes and complexity, there of course needs to be some flexibility in a system. You can’t treat all grants as equal and subject them to the same level of quality assurance – this would choke the system. What should be required for a grant of NOK 1 million should not be the same as for a grant of NOK 100 million. Proportionality is key. Our suggestion was that a financial threshold should be used where grants above a certain amount receive formal QA, while those below are QAed through a different approach. Alongside this we also recommended that the central Quality Assurance department is better resourced to conduct its quality assurance of results frameworks, and for a new cadre of results advisers to be created that sit within teams that can provide more informal technical support and QA to smaller sized grants.

The importance of routine monitoring data to good evaluation

One of the main drivers for this evaluation was the finding by the Norad Evaluation Department that in 2011 none of the studies and evaluations they commissioned could demonstrate results at outcome and impact level – they were able to say what activities were delivered, but couldn’t say what difference this made to the lives of poor people in developing countries. What became clear through the evaluation was that this was inevitable given the patchy treatment of results measurement at grant level. If results were not being consistently monitored at grant level, it was nigh-on impossible for the Evaluation Department to conduct robust strategic evaluations looking across multiple grants. Good evaluation is difficult (and costly) in the absence of good monitoring data. For me, this raises a broader issues related to the current debates around ‘evidence based aid’: while there has been much discussion around improving the number and quality of evaluation this has possibly been to the neglect of driving up standard in routine monitoring. Solid monitoring data makes evaluation much easier to conduct .

The evaluation of Norway’s results system seems to have generated a lot of debate within Oslo. We presented the report to a packed auditorium in Norad (Power point slides from the presentation are below), there was coverage in a number of the Norwegian newspapers (here and here) (in Norwegian) and a radio debate between a member of our evaluation team, the Director of the Norad Evaluation Department and the State Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (you can view the debate here – again in Norwegian). The report has also been picked up and commented on by Marie Gaardner from the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group and an Ex-Director of Norad’s Evaluation Department (see here). Hopefully the debate around the report will continue and we see some changes to how the results measurement system works. It is in everyone’s interest – including the beneficiaries and Norwegian tax payers – that it does.