Itad is working with the British Council and the Premier League on an innovative project, funded by the UK’s Department for International Development, which aims to tackle violence against women and girls through football.

The three-year programme is working to change inequitable attitudes towards girls and women among communities in Western Kenya. It is doing this through a combination of football and interactive education sessions with young people, and advocacy activities at a community level. The hope is that the programme will help reduce violence and, more broadly, empower girls and women to claim their economic rights.

As the monitoring and evaluation partners on the project, Itad has recently finished writing up the baseline findings. We spoke to young people, adults, community leaders and service providers in two communities – Kopsiro and Kapsokwony – on the slopes of Mount Elgon, where the programme is just starting its work. Our household survey, focus groups and interviews gave us some important insights into the severe challenges faced by girls and women in these two communities, and some ideas about what this might mean for the programme. We hope to make the full report public soon, but for now here are some of our emerging findings…

1. Violence is very common in both communities, and some forms of violence are clearly linked to inequitable attitudes towards women and girls.

Many community members believe that certain types of violence are sometimes acceptable – in particular that it is OK for men to beat their wives and parents to beat their children. Women are generally viewed as inferior to men (and sometimes even equated with children). This feeds into a number of attitudes that may contribute to violence within intimate relationships; including the belief that men have more right to decide about when and whether to have children than women do, and the widespread attitude that men have a right to sex with their wives.

Attitudes about masculinity and male sexuality may also contribute to violence – both men and women thought that men sometimes force women to have sex because they cannot control themselves, and that men need sex more than women do. Although somewhat less apparent, there also appear to be connections between ideas of masculinity (associations with strength and security) and the acceptability of violence between men in the community as a way of responding to insults or dealing with challenges (for example, arguments over land or other resources). Overall, we found strong evidence for the link between attitudes and violence theorised by the project, which confirms the importance of the programme focus on harmful attitudes, and gives some insight into areas the programme might hone in on through its community advocacy work.

2. That said, people living in Kopsiro and Kapsokwony also painted a vivid picture of the other factors that contribute to violence in the area.

There is a history of conflict and insecurity in the area, which is still manifesting itself in violence and has also contributed to a system of informal justice in which punishment is meted out by community members to offenders. Poverty is a central factor: violence within families and between community members is often fuelled by poverty and corresponding arguments about resources, land in particular. Poverty also pushes girls into risky economic and domestic activities (such as collecting firewood in the forest), which puts them at risk of sexual attacks. People also told us that violence between husband and wife, parent and child, and wider community members is often driven by alcohol use.

Inequitable attitudes are therefore just one feature in a kaleidoscope of embedded issues that contribute to high levels of VAWG. This should inform expectations about what it is feasible to achieve within the resources and time available for the programme.

3. Sexual violence is common and associated with high levels of stigma and shame, but it is not viewed as ‘acceptable’. This suggests the need to focus on violence within relationships as well as stigma and discrimination experienced by survivors.

Rape is not widely talked about in Mount Elgon, and often goes unreported. There was little evidence that (extra-marital) rape is considered at all acceptable within the community as a whole. However, lots of people told us that girls and women do not report it because survivors face severe stigma and discrimination, including rejection and difficulty finding a husband. There are also some signs that rape is blamed on the victim, for the way she dressed, or because she was drinking or going out with boys. Stigma also surrounds unmarried relationships. Girls frequently enter relationships with boys and older men (and poverty is one of the drivers of this too, with girls providing sexual favours in response for money or gifts from men), but this is disapproved of and girls are punished by parents if they find out. This feeds into the stigmatisation of early pregnancy, and the blame and disadvantage girls face if they get pregnant.

Rather than emphasising the unacceptability of rape – something that community members know very well – this suggests a clear need for the programme to instead focus on mitigating the shame and stigma faced by survivors, which results in girls and women feeling unable to report sexual violence. The programme may also consider challenging the widespread belief that men have a right to sex with their wives. This belief may feed an attitude that rape within marriage is permissible, as well as affecting boys’ attitudes towards their girlfriends and beliefs about sexual consent.

4. There are opportunities to build on existing positive attitudes, particularly around early marriage, education, and concepts of masculinity.

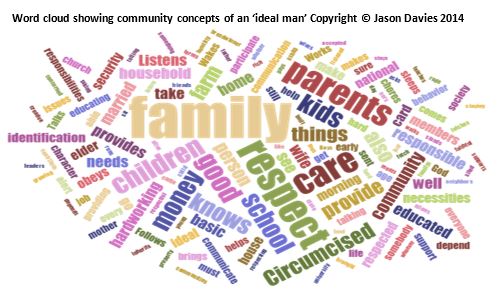

Having respect, including for women, is already seen as a central characteristic of being an “ideal man” and one which the programme could leverage in its messaging. Similarly, although attitudes are still not wholly equitable and girls and women still face significant disadvantages, the fieldwork suggests that attitudes towards women in leadership are changing and that education is valued for girls as well as boys. This suggests that is not necessary to launch a concerted campaign to change attitudes towards early marriage, equality of education or women in leadership. Rather, it may be more fruitful to focus on entrenching and deepening existing positive beliefs, and communicating about the enabling factors that help girls stay in school.

5. Messaging around services should be mindful not to simply encourage formal reporting of violence, given the obstacles inhibiting people from using formal mechanisms.

There is little evidence that girls and women do not seek help when they experience violence because they don’t know what to do or where to go. Other factors are far more significant, including negative perceptions around the quality of justice and health services, fear of stigma or adverse consequences, and recourse to more informal mechanisms of justice. Cases of rape or domestic violence are often dealt with through chiefs and village elders, as well as informal community compensation mechanisms. Simply encouraging survivors to report violence to the police and bypass these other channels could potentially have negative consequences, especially as police and health workers face severe challenges in terms of the resources available and their capacity to respond effectively and sensitively to violence.

6. Finally, it will be important to work on the attitudes of community coaches too.

A significant minority of the community coaches (local women and men recruited by the programme to deliver coaching and education to young people) believe that girls are partly to blame if they are raped and that there are times when a woman should be beaten. Most coaches also expressed approval towards physically disciplining children. This finding is not necessarily surprising, as the coaches’ attitudes reflect those of the wider society in Mount Elgon. However, it suggests that more work is needed to change the attitudes of some of the coaches, and highlights that it is important not to assume that the coaches are fully on board with the programme aims, just because they are willing to participate in the programme and have gone through the training. Project staff are responding to this challenge by providing ongoing training and support for the coaches, with the aim of shifting their attitudes gradually as the programme rolls on.

Look out for our next blog with updates from the programme, later in the year…..

Emma Newbatt and Melanie Punton, January 2016