We’ve just published a case study based on a fascinating week in Nigeria last summer, exploring what ‘adaptive programming’ looks like in PERL (the Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn), a flagship £100 million DFID-funded governance project.

Adaptive programming or adaptive management has rapidly become the new zeitgeist in  international development, along with its close relations Doing Development Differently, Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation, and Thinking and Working Politically. These approaches sprung up as a response to disillusionment towards rigid, pre-designed, blueprint, linear programmes, which have repeatedly failed to deliver the results they promise. But what does it actually mean to ‘work adaptively’? And does it work? As a partner in the IDS-led Action for Empowerment and Accountability research project, we have been exploring these questions – looking at whether and how adaptive approaches help promote and strengthen Empowerment and Accountability in fragile, conflict and violence-affected settings.

international development, along with its close relations Doing Development Differently, Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation, and Thinking and Working Politically. These approaches sprung up as a response to disillusionment towards rigid, pre-designed, blueprint, linear programmes, which have repeatedly failed to deliver the results they promise. But what does it actually mean to ‘work adaptively’? And does it work? As a partner in the IDS-led Action for Empowerment and Accountability research project, we have been exploring these questions – looking at whether and how adaptive approaches help promote and strengthen Empowerment and Accountability in fragile, conflict and violence-affected settings.

The PERL case study was the second of three (the first, a fascinating exploration of the Pyoe Pin programme in Myanmar, is here). DFID sees PERL as the final stage of a 20-year investment, building on 15 years of DFID-funded governance programming in Nigeria. PERL aims to adapt constantly, through a ‘living’ theory of change, continuous political economy analysis at different levels, adaptive implementation by location-based delivery teams who are encouraged to be flexible and let partners take the lead, regular learning and reflection, and adaptive resourcing, HR and administrative systems. All with the aim to improve the delivery of public services and goods to citizens.

Here are three things we learned from our week in Nigeria with the PERL team:

- Adaptation is not just possible but necessary – although never easy – in complex, fragile and diverse environments. There are vast differences between levels of conflict and fragility across the regions and states of Nigeria. Where there is conflict – like the North East, where the Boko Haram insurgency continues to pose a threat – linear planning is impossible, as the context and priorities with it shift so rapidly, quickly making ‘step by step’ reform approaches redundant or unworkable. Working adaptively allows PERL to apply different models of engagement in response to varying levels of fragility and commitment to public reform, addressing immediate conflict in some areas, post-conflict and recovery in others, and supporting development-minded reform agendas where conditions are more stable. PERL staff also feel strongly that Nigeria’s unique makeup demands an approach that can accommodate diverse voices and help find consensus solutions to problems. “We have many fault lines in Nigeria…religious, ethnic…they divide people. If you bring solutions to them, the solutions will not bed down. You have to work together in finding those solutions, for them to sustain.” However, while PERL staff told us that working adaptively is felt to be the only way to make progress in Nigeria, they stressed that it is still ‘fantastically difficult’ to make an adaptive programme work in complex fragile and conflict-affected environments. Adaptive programming is no magic bullet.

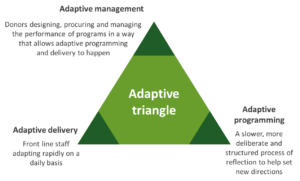

- People matter most. Our week in Nigeria showed us that the most important ingredient for adaptive programming is getting the people right – with a specific combination of skills, networks, credibility, emotional intelligence and a sense of ‘mission.’ But different skill sets are needed in different roles within an adaptive programme like PERL. We used the concept of an ‘adaptive triangle’ to unpack this:

- Adaptive delivery is what happens at the ‘front line’. It involves PERL’s state and national delivery teams and partners (civil society, government, citizens) applying curiosity, evidence and instinct to learn, adapt and make decisions in the short term. To do adaptive delivery, staff need more than technical skills – they need to be emotionally intelligent, comfortable with ambiguity, and have the soft skills to facilitate, influence, motivate and manage relationships with partners with humility and without money. They need to be intuitive and

instinctive, read signals, and be ‘good dancers’ within the system. We were told that often, the right people are ‘insiders’, “known as being objective and relatively apolitical and neutral, respected for not being too one-sided.” Getting the right staff is often essential for getting the right government and civil society partners, as personal networks provide crucial entry points. State Governors hold huge amounts of power in Nigeria’s decentralised political system, underlining the importance of strong state-level relationships, managed by staff who are embedded in the locality and are intimately acquainted with the context and key players.

instinctive, read signals, and be ‘good dancers’ within the system. We were told that often, the right people are ‘insiders’, “known as being objective and relatively apolitical and neutral, respected for not being too one-sided.” Getting the right staff is often essential for getting the right government and civil society partners, as personal networks provide crucial entry points. State Governors hold huge amounts of power in Nigeria’s decentralised political system, underlining the importance of strong state-level relationships, managed by staff who are embedded in the locality and are intimately acquainted with the context and key players. - Adaptive programming is what happens at PERL’s head office in Abuja. It concerns the more formal processes required to promote and support adaptive delivery – tools, support and structures to support and hold accountable the people doing adaptive delivery, as well as HR and M&E. Adaptive programmers need two sets of skills: on the one hand understanding and supporting delivery teams, with humility, patience, and trust; on the other hand ‘buffering’ delivery teams from donor structures, requirements and demands that can constrict adaptive working.

- Adaptive management in PERL’s case is DFID, and how DFID staff design, procure, fund and manage performance in a way that allows adaptive programming and delivery to happen in practice. This often requires a champion. PERL’s existence as an adaptive programme owes a lot to a DFID Senior Reporting Officer who was willing to ‘stick his neck out’, and was able to navigate DFID systems in order to get PERL off the ground as an adaptive programme, and who had the experience, confidence and charisma to take a risk and champion adaptive ways of working in the face of institutional challenges.

- Being politically savvy means understanding donors too. Political economy analysis is at the crux of everything that PERL does, helping front line staff to ‘chase the problem’, respond rapidly to the context and challenges on a daily basis, and then test and correct these decisions. But staff told us: “We work on the political economy of DFID, as much as on the political economy of Nigeria. That’s how we’ve survived.” While smaller adaptive programmes can sometimes ‘fly under the radar’ in order to experiment and innovate, the opposite is true for the £100 million supertanker that is PERL. This means that PERL’s management team in Abuja needs to be able to understand and navigate the pressures that DFID faces to demonstrate results for accountability, in order to protect space for adaptive delivery. A big part of this is ensuring monitoring and evaluation systems can demonstrate results without becoming a straightjacket for delivery teams. PERL’s M&E system is very sophisticated, emphasising narrative and qualitative evidence and using outcome harvesting and various scales to capture and communicate evidence of change and contribution. However, this has created a huge bureaucratic burden for delivery teams, and it is an ongoing struggle to ensure that learning is appropriately incentivised.

Read the case study for more – and our thanks to PERL for giving us such a fascinating insight into what adaptive programming means in Nigeria. Our final case study – on I4ID in Tanzania, and a synthesis paper drawing together insights from the set, will be out soon in 2019!