With the virus seemingly yet to take hold in much of the developing world, and cases emerging in countries already crippled by instability1, how does development and humanitarian programming respond to a complex, changing and, as yet, largely unknowable situation?

We hear a lot that governments and organisations will be ‘guided by evidence’ as they respond to the pandemic. This has long been a tenet of development and humanitarian programming, and is even more important in these challenging times. Here at Itad, all our practices (and indeed, our operations teams as well) have been grappling with what the pandemic means for the people, partners and programmes we work with and how we work with them.

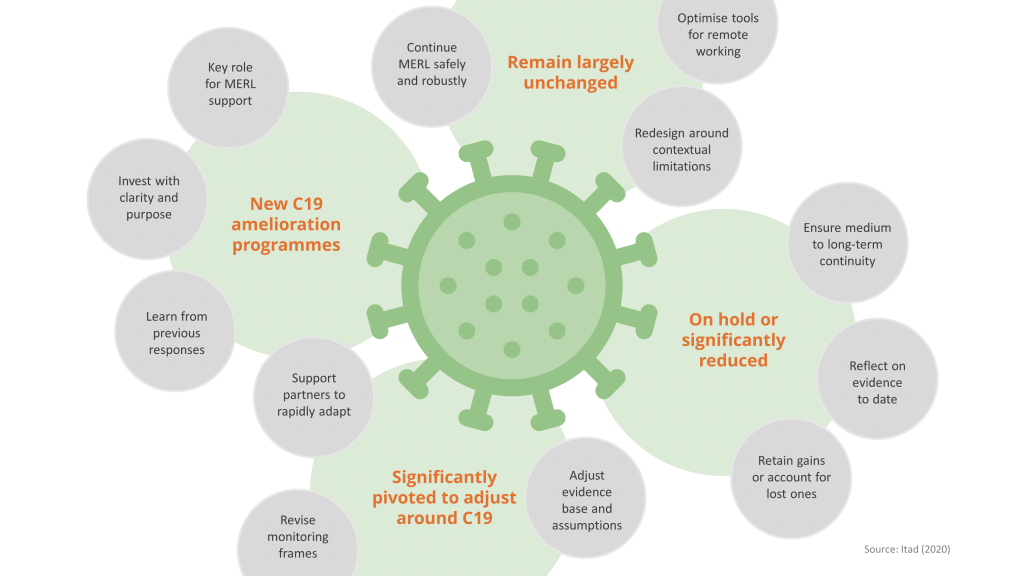

We believe that being guided by the evidence is essential to ensure programmes are still having an impact and delivering results, learning and adapting in real time, and are sustainable in the long term, whether that be:

- Operationalising existing evidence to promote the sustainability of programmes curtailed during the pandemic.

- Using evidence to inform or improve implementation of continuing programmes.

- Rapidly generating evidence to be used in the here and now to help programmes that need to pivot and adjust.

- Using evidence to inform the design of C19 amelioration programmes.

With this in mind, we’ve been reflecting on our experience over the last few weeks, and on the 35 years we’ve been conducting monitoring, evaluation, research and learning (MERL), to help our partners respond and adapt in these challenging times.

Design and implementation

We know that even in cases where programmes can continue their work reasonably close to ‘business as usual’, some adaptation is still needed in response to C19. To continue to supply evidence, we have to ensure that our MERL work can still be done safely and robustly – be this through remote data collection, more qualitative-focused interviews or interactive workshops facilitated online. For example, the Adolescents 360 process evaluation is currently pivoting from in-person to fully remote data collection, through phone interviews with national and community stakeholders across Nigeria, Tanzania and Ethiopia.

Similarly, with the plethora of apps available to support remote working, we’re seeing encouraging and exciting results as we experiment with our partners in using virtual post-its, online whiteboards and other visualisation tools across multiple locations and time zones – lessons from which will be the subject of a future blog, so watch this space.

In some of these cases, we may also need to redesign our evaluation approaches to best deliver robust evidence whilst recognising the limitations of the current context, for example through reduced targets, and a narrower scope and focus. We also need to consider whether our work will place an unnecessary burden on potentially already-stretched teams. In these instances, we need to refocus on the data we require in order to effectively do our work and work out the best approaches for surfacing it. We have to ask whether we are putting ourselves, our partners and the people we seek to help at risk with our activities, and adapt what we do to mitigate against them.

Adaptive management and rapid evidence collation

Despite the dominance and urgency of the pandemic, it is widely recognised that many aspects of development and humanitarian programming must continue to deliver on key developmental outcomes and ensure basic human rights are addressed – see our blogs on education and SRH programming in the time of C19 for more insights. Active MERL is crucial to help ensure that these ‘C19 pivoted programmes’ are as effective as they possibly can be. This may involve rapidly adjusting and testing the evidence base and assumptions behind new theories of change for revised programme designs, and developing revised monitoring frames to generate real time information on how adjustments are working (or not).

Many countries and organisations have or will commit to funding programmes that target the effects of C19 in the developing world2. We know that our partners will want to move quickly to respond, but it is critical that these investments are made with clarity and purpose, to ensure that needs are met and the broader implications of the pandemic are taken into consideration. Lessons from previous responses to health emergencies and natural disasters are crucial in this context. For example, our evaluation of DFID’s humanitarian response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines found that resilient recovery requires time, local knowledge and trusted local relationships. There is a wealth of evidence from the Ebola response in West Africa which emphasises the importance of thinking early about recovery and ‘building back better’.

We’re working with our partners to rapidly interpret and operationalise this learning, and draw on good practice from previous crises, to enable them to make evidence-informed decisions about ongoing adaptation or the design of new strategies and interventions, as well as think through both the short- and long-term consequences of the pandemic in a particular context.

Time for reflection

Some programme interventions may not be compatible with C19 mitigation measures (e.g. NTD programming3) or may require extensive international travel not possible in a locked-down world. In most cases, where a programme has been postponed or activities significantly scaled back, the priority is on ensuring the continuity of these interventions in the medium to long term. This time can provide an opportunity to reflect on evidence gathered to date. The AVANTI Initiative, for example, is using this time to focus on the knowledge component of the project – drawing together lessons from implementation to date and using this to improve methodology for the future.

Other projects, which have been paused entirely, present us with a clear challenge to ensure that when programming restarts, the gains that were made prior to C19 are not lost, and, in cases where they have been lost, we are able to account for this in the (re)design of the programme. Again, where possible, MERL can help – in tracking the (most likely, negative) impact of C19 on programme outcomes and help input into a design of the ‘reboot’ of the programme which takes this to account. In addition, there may also be lessons to be drawn from evaluative opportunities presented by programmes stopping and starting, and reacting to a major shock like C19.

Evidence is crucial – now and in the long term

Monitoring, evaluation, research and learning, and the evidence produced as a result, must play a key role in ongoing and future programming in response to COVID-19. Over the course of the next few weeks, we’ll be sharing insights from our work across the organisation – from how we are doing our work remotely to how we are adapting our work for the longer term. Our practices will also reflect on what the pandemic means in their particular areas of focus, to help join the dots and ensure an interconnected response to a global crisis.

Credit:

This blog was written by Emmeline Henderson and Sam McPherson with contributions from Jo Robinson, Ethel Sibanda, David Fleming, Ed Hedley, Richard Burge, Rachel Eager, Chris Barnett, Stef Wallach, Mel Punton and Katherine Gibney.