Itad has been providing evidence and learning support to the UK CSSF (Conflict, Stability and Security Fund) since 2015. Our work is focused on helping the Fund measure the effect of a cross-government response to preventing conflict and tackling threats to UK interests arising from instability in the region. We present here insights from developing and rolling out a framework and toolkit for measuring PAI, and reflections on how this could be more widely applied by other donors, agencies and implementers working in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

What do we mean by PAI and why does it matter?

Delivering results can be unpredictable, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected settings, and often requires an understanding of who the key individuals or groups are with power and agency in a specific context, what their interests and incentives are, and how these can be engaged to influence decisions. Political access, therefore, provides entry points for engagement with and influence on key decision-makers in pursuit of shared objectives.

As a cross-government fund, the CSSF enables the UK government to address complex stability and security issues in an integrated way. It delivers programme activity that complements and utilises the relationships the UK government holds with other governments, donors and security forces to respond to crises and opportunities as they emerge and to leverage strategic effect. Generating and maintaining PAI to achieve goals is therefore critical to success.

The CSSF PAI framework and toolkit

Interventions in conflict settings that can help build PAI – e.g. an adviser embedded in a host government ministry, or training provided to local security forces – often need to be adaptive given the highly politicised and volatile contexts in which they are operating. As such, more traditional monitoring and evaluation tools – including accountability-focused results frameworks – are less helpful in capturing PAI achievements and learning.

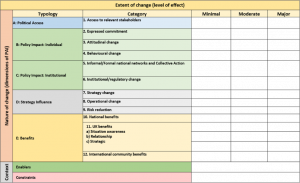

To respond to this, we have developed a toolkit for measuring PAI across CSSF programming. This consists of a framework and set of practical tools to enable CSSF teams to monitor and assess the nature and extent of access and influence gained through programmatic investments, and the results this has contributed to.

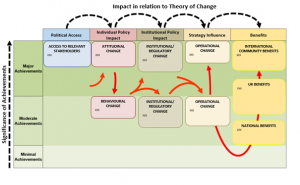

The PAI framework (figure 1) is based on a simple theory of change that links political access to influence on individuals, institutions, strategy and operations, translating into benefits for the UK, host country and the international community. It is designed to be flexible and easy to use, enabling CSSF teams, implementers and seconded advisers to collate and organise evidence of both the nature and the extent of the PAI change (by categorising achievements as minor, moderate or major).

For example, the work of a UK advisor to help strengthen a host country’s institutional capability to prosecute serious crime may generate PAI that contributes to:

- Expressed political and professional commitment of key national counterparts to work with the UK on criminal justice reform;

- Institutional/regulatory change in the form of increased financial and human resources in support of implementing commitments;

- Strategy and operational change in the form of increased capacity to prosecute serious crime, and improved interagency cooperation between the two countries;

- Benefits to the host country and the UK in the form of a more effective national system for processing high-profile criminal cases, including those in the UK’s interest.

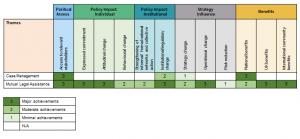

Evidence recorded in the framework can then be analysed over time to support reflection, learning and adaptation. Alongside the framework, we have developed stakeholder mapping and analysis tools that identify key actors according to their level of agency within an institution, and the level of access and influence currently held by the UK; and a set of communication and reporting tools including a PAI heat map and change pathway diagram (figure 2) that help to tell the story of change enabled by PAI in a visually compelling way.

Insights and lessons

We have tested the CSSF PAI framework and toolkit across a range of UK government programming contexts in Eastern Africa which pioneered it, and have found it to be valuable for CSSF teams for a number of reasons:

- Provides valuable insights into how CSSF programming contributes to results. PAI is often an important enabler of change for CSSF programmes, and the PAI framework can help to make that linkage explicit. For example, it was used to demonstrate how political access and influence generated by the UK criminal justice advisor in Kenya helped to strengthen mutual legal assistance between Kenya and the UK, providing a strong foundation for cooperation between the two countries around criminal prosecutions.

- Enables CSSF teams to identify how to engage actors who can influence the achievement of objectives. As well as being used as a monitoring tool, the PAI framework is also valuable at the programme design stage. Given the often unpredictable nature of change brought about through PAI in fragile settings, adopting a PAI approach at the outset of an intervention can help to identify and track different influencing approaches and pathways, recognising that whilst some may be ‘dead-ends’, others may have very unintended and positive results.

- Helps identify and understand the changing dynamics between programme and political goals, and incentives of different actors to achieve them. A number of PAI case studies from Eastern Africa have demonstrated the mutually reinforcing nature of programme and political diplomacy work, with examples of successfully preventing and disrupting Serious Organised Crime in Tanzania and Kenya.

- Provides a structured and systematic approach to collating PAI evidence. Whilst the simplicity of the PAI toolkit has been a strength in enabling CSSF teams to take a more systematic approach to data gathering and analysis, one frequent challenge has been the difficulty in verifying self-reported achievements, especially because PAI objectives are not always expressed overtly. The PAI framework provides a transparent means for identifying informants, recording data sources, and helping to identify where triangulation would be most important. However, like any monitoring tool, the strength of confidence in the findings depends on the reliability of the data, and the extent of verification and triangulation.

Reflections on the way forwards

Since completing our first set of PAI case studies in Eastern Africa – which demonstrated the value of the framework not just for the region, but for the Fund more widely – we have supported teams across the CSSF network to embed PAI thinking and approaches across programming and to further develop the PAI toolkit. This has included developing a case study approach to analyse how and why change happens and to assess the contribution of PAI to change; embedding PAI analysis into programme and thematic evaluations, and helping to make PAI analysis an integral part of programme monitoring. We are also currently thinking through how value for money assessment approaches can capture the value of influencing.

Beyond the CSSF, the results of our work show that the PAI framework and toolkit are valuable for any donor or implementer seeking to develop a more purposeful approach to identifying influencing objectives, systematically tracking progress and better evidencing how PAI supports change, thereby filling an important gap in our MEL toolbox for working in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Feature image: Downtown Nairobi. Credit: millerpd/iStock

Our work on political access and influence was featured in a Devex article ‘How one UK government fund tracks its influence in fragile countries’ (paywall)