Itad, in cooperation with Pamoja, recently completed an evaluation of the Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA).

MeTA was a DFID-funded initiative, coordinated by Health Action International (HAI) and the World Health Organisation (WHO), and implemented in seven pilot countries (Ghana, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Peru, the Philippines, Uganda and Zambia) from 2008. The aim of the initiative was to improve access to essential medicines.

MeTA focused on promoting evidence-based policy making in the medicines sector through two key strategies:

- Transparency, by supporting the collection, analysis and dissemination of medicines supply chain data; and

- Accountability, by promoting multi-stakeholder dialogue between government, the private sector and civil society.

In implementing this model, MeTA took not a conventional technical approach to improving access to medicines, but a governance approach. MeTA is one example in the emerging suite of initiatives promoting multi-stakeholder approaches, such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the Construction Sector Transparency Initiative (CoST), or the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan, among others.

What did the evaluation do?

We focused on the governance approach taken by MeTA in our evaluation, with the main objective of assessing the role of transparency and accountability in evidence-based policymaking in the medicines sector.

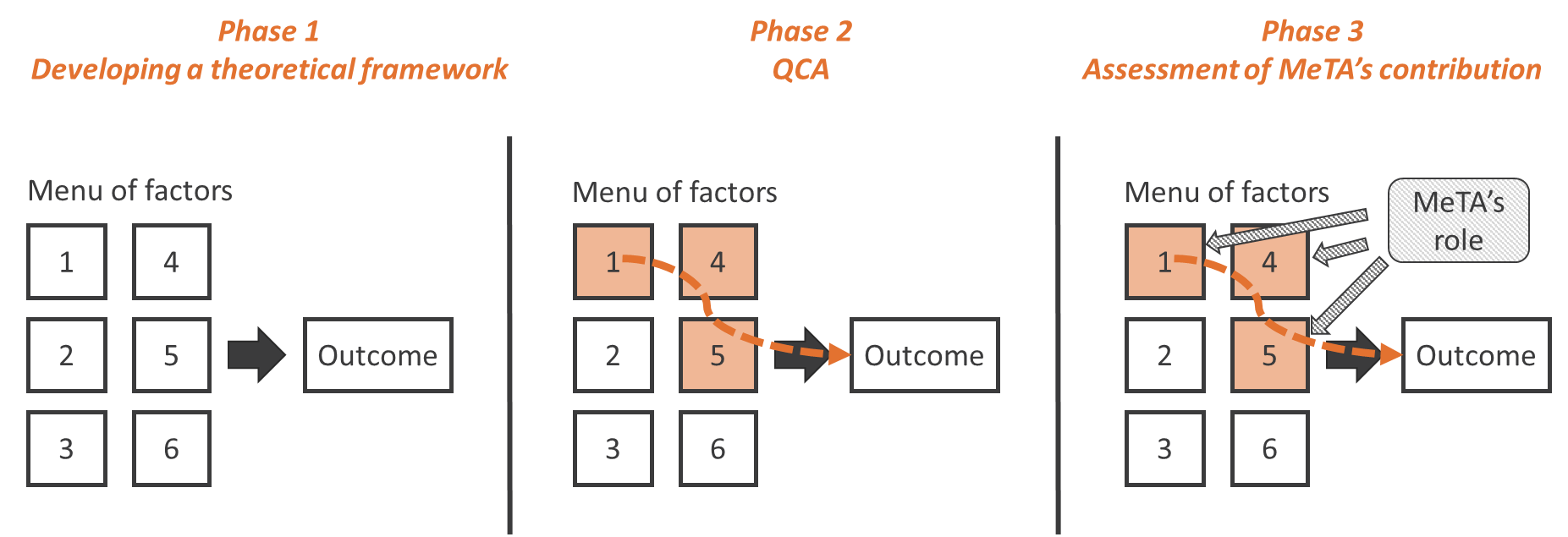

Our theory-based evaluation design was structured in 3 phases:

- Development of a theoretical framework to explain how evidence-based policymaking in the medicines sector occurs. This was largely based on John Kingdon’s agenda-setting theory and consisted of a ‘menu’ of factors looking to explain how policy making happens.

- Testing of our theoretical framework against the 7 MeTA countries by applying Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). This helped us identify which factors and pathways were crucial to MeTA’s success.

- Visiting 3 MeTA countries (Kyrgyzstan, Uganda and Zambia) and applying elements of contribution analysis to assess MeTA’s contribution to those factors we found to be critical during the second phase.

The 3 phases of the evaluation are illustrated below:

More details on the evaluation methodology can be found in the evaluation report. We have also included lessons from applying QCA in the MeTA evaluation in our recent CDI Practice Paper on QCA.

What did the evaluation find?

The evidence on transparency was mixed. When framed as collecting, analysing and disseminating data, transparency did not play a strong role. However, in practice, we found that it played an indirect role in providing stakeholders with relevant data to engage in multi-stakeholder dialogue in a credible manner. MeTA’s strength did not lie in its ability to generate data per se, but in how that data was used as an integral part of multi-stakeholder policy dialogue. Where data was used for general public awareness raising rather than to inform the multi-stakeholder dialogue, MeTA’s chances of policy success at country level were not increased.

Evidence was very clear in our main findings on accountability and the multi-stakeholder approach. We confirmed the value of the multi-stakeholder dialogue as a means of improving accountability and so evidence-based policy making in the medicines sector. MeTA’s multi-stakeholder approach allowed for constructive engagement of private sector and civil society, which led to improved policy making in the sector. Our evidence showed that open multi-stakeholder dialogue did not happen prior to MeTA, and that the initiative made a unique and significant contribution to it.

We also sought to unpack key ‘ingredients’ for a successful multi-stakeholder approach. We found that consistent stakeholder engagement and civil society capacity to engage were essential. Transparency and information sharing between all stakeholders, as well as rotating the chairing of meetings between stakeholder groups, were less important. Civil society capacity had to be developed where it didn’t exist, which meant that a long time horizon was required. Generally, we found this to be true for the multi-stakeholder approach to work, given the need for trust relationships to be developed.

Overall, our findings are in line with an emerging body of evidence on transparency and accountability generally: existing macro-evaluations and literature reviews suggest that the role of transparency is ambivalent, while most evidence points to the utility of building alliances between state and non-state actors. The MeTA multi-stakeholder platforms are such alliances, and our evaluation provides new evidence of their effectiveness.