Working as an international development professional in the last two and half decades, I began to see what looked like a rapid spread of corruption especially in public spaces and the seeming dichotomy between the informal and formal spaces in terms of sanctions. It would seem that the “rules” are different within different reference networks. So, for example, if “Politician A” steals money from government and builds a town hall in his community, it is seen as okay; but if the same person were an official of a village association and he stole, there would be serious sanctions.

UK Aid, through the Department for International Development (DFID), is supporting the Nigeria government through the Anti-Corruption Programme in Nigeria (ACORN), which aims at “a reduction in corruption as a result both of stronger incentives not to loot government resources and as a result of changing public attitudes that will increasingly disapprove of corrupt activities”. A pillar of the programme – Supportive Society and Social Norms – is seeking to change expectations and attitudes towards corruption in Nigeria. This pillar is tagged Strengthening Citizen Resistance Against the Prevalence of Corruption (SCRAP-C) and is managed by a consortium led by ActionAid Nigeria. I work for Itad, which provides specialist technical advice to the programme on monitoring, evaluation and learning. This blog explores major contextual issues around social norms and how the programme is seeking to catalyse behaviour change as part of the fight against corruption in Nigeria.

Social norms, behaviour change and anticorruption

A social norm is a rule of behaviour that individuals prefer to conform to because they believe that most people in their reference network: (a) conform to it, and (b) believe they ought to conform to it (Bicchieri 2016). SCRAP-C will analyse behaviours in relation to corruption, plus the reference networks and traits that allow conformity, with the aim of changing these and making corruption illegitimate.

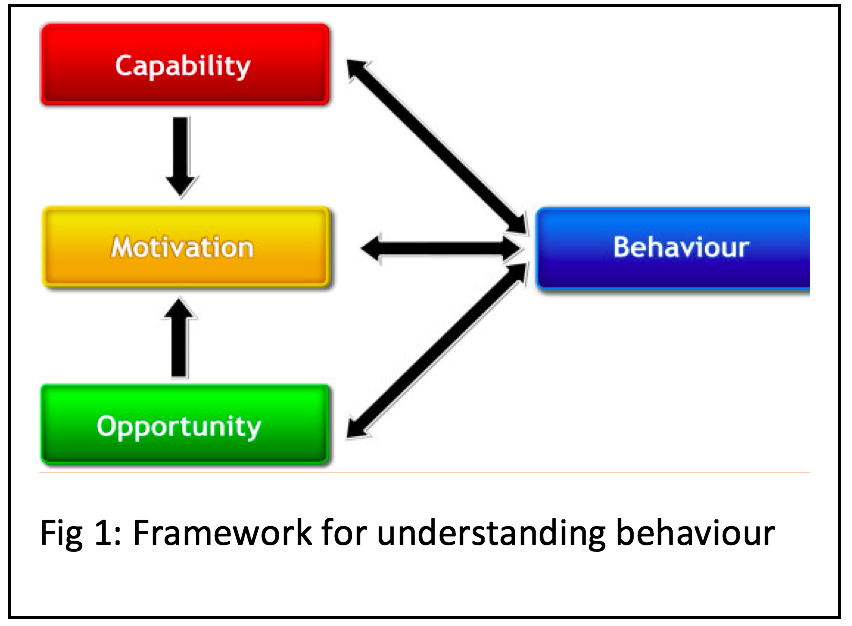

Adopting the behaviour change analytical model of COM-B (Michie et al., 2011), the programme is looking at the underlying capabilities, motivations and opportunities that drive people’s behaviours, and how these can be influenced positively in a way that disapproves of corruption. An important consideration is how reference networks influence these attributes.

In the sections that follow, I explore each of the traits.

The capability to understand and reflect on the complexities of corruption

Discussions about corruption in Nigeria are often quite narrow and limited to who is involved and where they come from. Thus, the capacity to see corruption as a broader issue that affects the whole society, is often lacking.

In order effectively to institute behaviour change, it is important to understand the complexities of corruption. The programme is working with citizen groups to help them look at corruption in a multifaced and holistic way – to explore behavioural traits such as lack of sincerity and accountability, or the use of religion, ethnic or political affiliation in the negotiations of socio-economic transactions. Critically, the programme is also helping these groups understand the impacts of corruption on service delivery (health, education, power) and the effective running of the Nigerian economy.

Understanding the drivers of corruption and what motivations exist or are prevalent, for corrupt practices to thrive

The combination of a lack of sanctions and the legitimising of corruption has led to its entrenchment across most communities in Nigeria. Such is the case where notable corrupt public officials are celebrated in local communities. A prevailing social norm seems to be that the abuse of public office for personal gain is acceptable, as are the misappropriation of public funds and influence peddling to meet societal expectations.

Ordinary citizens are very often unable to question public office holders because they make personal demands on them, pressuring them to indulge in corrupt practices. In many instances, constituents see public office holders as a source of funds for personal needs. A few sincere officials often state that constituents’ uncontrolled personal demands hinder them from carrying out their functions effectively, requesting monetary support for anything from marriage ceremonies to hospital bills.

Through its work with citizen groups, the programme is raising consciousness that making personal demands diminishes the ability to hold public office holders to account, whilst increasing motivations to be corrupt.

What opportunities exist to engage in corrupt practices?

The quest for political power in Nigeria has had a huge impact on corruption. Such power, linked to the control of resources, has resulted in the perversion of rules and the creation of a small but complex elite network with access to and control of the national wealth. This network cuts across business, political, public and private sectors. In the public sector for example, emphasis is placed on tribe, religion and other primordial considerations in the allocation of jobs, creating a patronage system upon which corruption thrives.

The project is centred on creating an evidence base that highlights the impacts of these systems on the deepening poverty in the country. By tracing the links between patronage politics, mediocrity in public and private sector activities and poor service delivery, the project seeks to galvanise collective action against these practices. The message is for citizens to not give politicians the opportunity to use tribe, religion and other financial inducements to gain access to public office.

How are we monitoring the changes we would like to see?

As with many similar initiatives, attribution or proving the causal links between activities and behaviour change can be complex. Itad is supporting the programme to create a strong learning stream, which designs, manages and systematically drives cyclical testing and reflecting.

In building the evidence that will be used to make these connections, we are using the programme theory of change. On an on-going basis, Itad will be supporting the programme to distil lessons on how initiatives like social accountability/social audit mechanisms, capacity development, or awareness raising have influenced behaviours in relation to the rejection of corrupt practices. It will also include lessons on how specific practices are resulting in any collective actions to influence the changes.

In line with the COM-B approach, changing behaviour and facilitating information to correct misconceptions about what others think is critical. We also recognise that just putting information in the “public domain” may not necessarily equate to localised action at the community or household level. Itad is supporting the programme to explore questions such as how information provision is leading to awareness, and ultimately shifting behaviours that legitimise corruption to those that sanction corruption.

The programme will use qualitative research to gain an understanding of underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations around citizen acceptance of corrupt practices. This includes factors such as values, enablers or barriers to sanctions; and how or why capacity enhancement has affected knowledge, attitudes and practices to drive changes in behaviours. Perception studies will be used to capture behaviour changes – what people report has changed regarding corruption in the opinions of their families, friends, neighbours and other citizens. We will also focus on peoples’ experiences: what they have witnessed, experienced or what they know about anticorruption efforts, and capture knowledge/attitudinal change resulting from their exposure to the SCRAP-C.

This blog was originally posted on the Public Administration Review website here.