RCTs as a gold standard: an idea that won’t die? Melanie Punton

In her brilliant and provocative keynote speech, Zenda Ofir asked us: which evaluation ideas must die, in order to meet the huge challenges our world faces in the next years and decades?

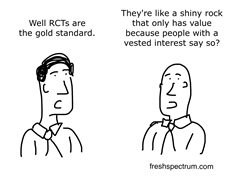

One idea that seems to have been dying ever since I entered the evaluation world is the idea of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) being the most appropriate approach in all circumstances. This was challenged in 2012 in an influential DFID working paper, and every evaluation conference I’ve attended since seems to re-emphasise the importance of choosing an approach that suits the question being asked, rather than defaulting to the idea that RCTs are the ideal option and everything else is second best.

At this year’s conference, a lot of conversations were about the challenges of evaluating complex programmes in complex, shifting environments, and the need for evaluation to support rapid, real-time learning and adaptation – two things that RCTs are not great at. But the idea that RCTs are the ‘best’ approach is still widespread – for example, the very useful EVIRATER framework developed by Abt Associates provides a framework for rating research evidence, which again puts RCTs and quasi-experimental approaches at the top. Why is this? In part it reflects sectoral and geographical differences – DFID has been particularly good at supporting innovative, non-experimental evaluation approaches – but it also seems to link to deeper, sometimes implicit assumptions about what ‘good’ evidence looks like, which come from the same line of thinking as RCTs – for example, you need to have a control group, you need randomisation, perceptions data can’t be trusted. Alternative models of causality question these assumptions, and at the conference, we discussed the potential of realist evaluation and process tracing to establish robust evidence of programme effectiveness through a very different mode of reasoning and assessment (e.g. our evaluation of BCURE). We need to keep having these conversations and challenging these assumptions, which do not look like dying any time soon!

Thinking systemically about evidence use. Ed Hedley

UKES 2018 contained several useful presentations on the role that evaluations can play in informing evidence-based policy-making. Annette Boaz, Professor of Health Care Research at Kingston University and St George’s University of London, gave a thought-provoking keynote address on the relationship between evidence, policy and practice. She structured her presentation around the work of Best and Holmes (2010) who provide a framework to understand how this relationship has evolved over time, from first generation linear approaches, to second generation relationship models, and finally to third generation systems models. Annette argued that our thinking has evolved from an earlier focus on products, which are important but not sufficient spark evidence use, to an understanding today of the value of relationships and different ways of working with stakeholders. The next frontier she argues will be to deploy systems thinking to explore more comprehensive ways of tacking the challenge. This is starting to emerge through concepts such as co-producing knowledge but, she argues, has yet to become truly transformative, which may include empowering stakeholders to produce their own knowledge.

This shift to systems thinking seems to resonate with DFID and other donors’ desires to move towards increased partner-centric and participatory approaches in the production and use of evidence but suggests that further thinking is needed to ensure that this shift is more than mere window-dressing.

Translating evidence into use: a priority for evaluators. Claire Hughes

For me, the takeaway message from this year’s UK Evaluation Society Annual Conference is to give the translation of evidence into use much more serious and early consideration in the work that I do. In the work that I do, I regularly see clients wanting programmes to help ‘build the global evidence base on….’. But what does that really mean? Who wants the evidence? What evidence do they need? And how do they want to use it?

As monitoring and evaluation specialists, this vagueness on the part of our clients often gives us some welcome leeway: it avoids the need to make specific commitments to translating our evidence into use, at a time when we have no idea what our evidence will say. But to maximise the potential of the evidence we generate, we need to be bolder. We need to grasp the opportunity presented us, and challenge the commissioners of the work that we do to be more specific about their own objectives for translating evidence into use and how those objectives can be achieved: the specific stakeholders with an interest, the potential windows of influence, the role the commissioner can play in encouraging others to use the new evidence. Importantly, we need to encourage commissioners to be realistic about the timelines involved in generating strong evidence – especially if it is evidence about what works for long-term processes like behaviour change – and ensure that the sharing of the consolidated end of programme evidence is not curtailed by inadequate time and resources. And then the emerging plan of action needs to be actively pursued and managed, building relationships with stakeholders, evolving plans as opportunities for influence open and close. Is this a role of M&E specialists? For some, yes, but probably not for all. But as people with an interest in seeing the evidence their work generates being used, we can certainly play a role in ensuring the teams we work within are equipped to effectively communicate the results of our work in targeted and engaging ways.

Adaptive, flexible evaluation…aren’t we really talking about how we respond to learning throughout the evaluation? Aoife Murray

Adaptability, flexibility and learning were all concepts that arose during a number of sessions at this years’ UKES conference. The conference theme focused on the quality of evidence – however, the overriding importance of managing the evaluative process, ensuring that quality evidence is timely, relevant and usable is fundamental to a successful evaluation. More often than not, we lose sight of the intended use of evidence and continuous need to ensure its relevance.

So, what do we mean by adaptive evaluation and how flexible are we to change during implementation? A key takeaway for me is the importance of the process – how do we implement the methodology and ensure its relevance as we conduct the evaluation? How do we ensure the findings will remain relevant and meet the needs of the intended users in changing environments? An interesting idea discussed was the application of ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ dissemination techniques. Balancing rigour and usability is key, while open, honest dialogue with the intended users should be a prerequisite for adaptive evaluation. The challenge of ensuring that high-quality findings remain relevant and timely for the user in practice undeniably requires astute management of the evaluation process.